With the news that Tesla's sales are down by 45% in Europe, you’d think that electric cars are a hopeless endeavour. If you search the internet you find stories of their batteries catching fire, there aren’t any charging points, and people don’t want to drive them with the whole concept seemingly being foisted on an unwilling public by monied elites.

The reality is very different. While it’s certainly true that sales haven’t exploded in the way some manufacturers would have liked, this isn’t an unexpected teething problem, and points more to the pace of government investment than any real problem with demand. Policies and opinions all point to a wealth of benefits for electric vehicles—and a very rosy future for anyone interested in trading and exporting them in Europe (except perhaps for Elon Musk.)

An electrifying start

There has always been a certain level of scepticism towards electric vehicles—or at least, since the last time they were popular. That’s because electric vehicles are far from a new invention; in fact, they were among the first vehicles ever made. Electric cars were invented in the 1830s, and became commonplace by the early 1900s, with more than 600 electric taxis operating in New York around the turn of the century. Rather than waiting to charge their batteries, they would simply go to a battery-swapping station to get a brand new one.

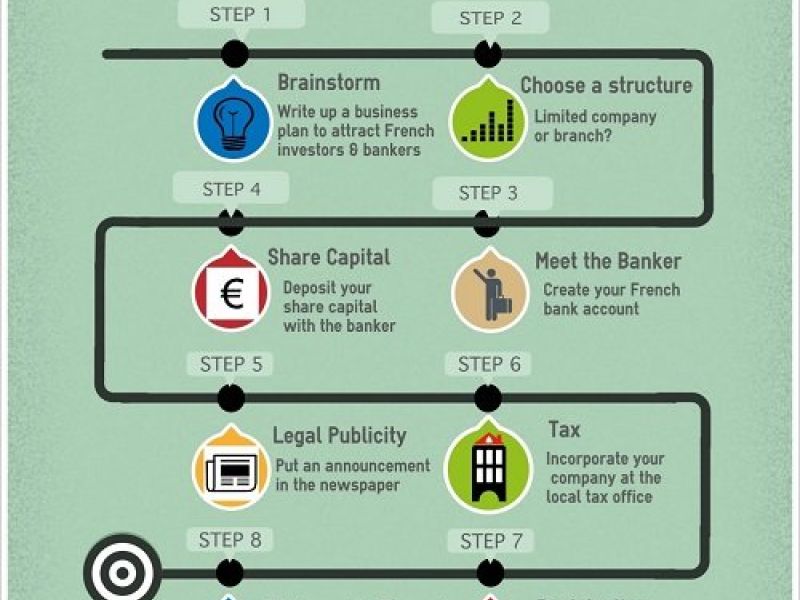

Related article: How to start a cleantech business in France

One of the ways electric cars were originally marketed was for their simplicity of use, and quiet operation in city centres. As opposed to combustion engines, electric cars didn’t require a hand crank to get started, leading them to be advertised to women. Unfortunately, the economics of combustion vehicles soon won out, with the Model T costing less than half of an average electric car during its first run, and only becoming cheaper from there. Electric vehicles clung on during fuel shortages, such as in the Second World War, but largely died out afterwards apart from in niche examples.

Despite efforts to drive up electric car usage, public perception in the years since has never quite gotten past this idea of more expensive and more restrictive travel. Petrol and diesel vehicles have a reliable network of stations to refuel at, and an enormous used car market means they are easy to buy at affordable prices, and just as easy to sell. Electric cars meanwhile have developed not only a perception of being more expensive and harder to refuel, but also less reliable and harder to repair—despite having many fewer moving parts.

The perception of electric vehicles

You would think that nobody was buying electric vehicles, from the way they are often depicted in the press. Yet the outlook is far from gloomy. Despite the previous UK government ending its electric car subsidies, sales of electric vehicles hit a new record in 2024, totalling 19.6% of all new cars sold. This is despite overall new car sales only rising by 2.6% last year, and still falling well below pre-pandemic levels. This also doesn’t include hybrids, which made up 13.4% of sales last year. The latest figures by the European Automobile Manufacturers' Association (ACEA) released this week also show that European sales of electric cars went up by 34% which is a 15% share of the total car market.

The massive fall in diesel sales—down from 31% six years ago to 6.3% today—shows how quickly the landscape of car sales can change. And while targets may be revised in light of lower sales of new cars, electric vehicles remain a key part of the UK’s net zero ambition, as well as that of other countries. Major cities across Europe remain bound to these pledges and to their own aspirations for better air quality, with London, Paris and Amsterdam all set to follow through on bans on petrol and diesel vehicles by 2030.

Related article: The French Tech Startup Ecosystem

The existing low emission zones in these cities are also massively incentivising the switch for a large percentage of the national population. After several years of increased electric vehicle uptake, older electrics and hybrids are also starting to pop up on the used car market, making them cheaper and more accessible. While electric car infrastructure is best around the capital, the number of people this impacts will get the ball rolling for everyone else, and help to demonstrate the efficacy of the technology.

Driving demand

A large number of manufacturers are also coming into the game and competing to drive costs down and improve quality, while breakthroughs on battery tech also appear to be on the horizon. New builds in the UK are tending to be built with electric charging points, all driving towards a future where electric vehicles are easier to transition to and remove the current perceived penalties of ownership (range anxiety of not being able to rely on charging while on the move, and slow speed of charging meaning you have to wait around).

Electric cars also offer an easier on ramp for new drivers, as they are all automatics. Automatic licences may become more preferential as a result, and could even alleviate the backlog of learner drivers and long waits for licenses, as automatics are easier for learners to drive than manuals. Having an automatic license will then help to drive people towards newer electric vehicles, rather than fossil fuel powered manuals.

The question that remains is who will step up to meet these new demands, and be able to harness this potential. We’ve seen how Tesla’s market share has fallen dramatically with the advent of cheaper and more reliable competitors, and with Musk’s extraordinary rise in power with the White House, it may result in a backlash in sales. As electric cars are often more traditionally bought by green-thinking, left-leaning customers, Musk’s controversial extreme right views may mean he has shot himself in the foot with that potential customer base, meaning the landscape could remain in flux for some time.

Traditional European car manufacturers have had to scramble slightly to develop electric alternatives, while concerns have been raised in Europe and the United States about the threat posed by Chinese electric vehicles, which may be difficult for others to compete with due to the possible involvement of state aid.

In either instance, there is a real opportunity for importers and exporters within Europe (except of course with the USA due to Trump’s new tariff proposals.) Outside of China, Europe seems to have the greatest current and potential demand for electric vehicles, with EU-wide net zero commitments, and multiple major cities promising to ban combustion vehicles. Countries such as France and Germany also remain car manufacturing heartlands, and the EU is planning subsidies and other incentives to drive up ownership—all potential boons for savvy entrepreneurs.

Electric cars may seem like a non-starter, but all of the evidence points to this being a bump in the road. The long-term prognosis remains that EVs continue to grow their market share as the EU in particular builds to a lower pollution, lower emission future—ideal for anyone in the business of manufacturing, importing or exporting electric vehicles.